November 3, 2025

4 min read

The U.S. Might Lose Its Measles-Free Status Soon

A meeting of the Pan American Health Organization this week will address the resurgence of measles in the Americas

A vial of the Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccination. The U.S. could risk losing its measles-free status if current outbreak trends continue.

PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images

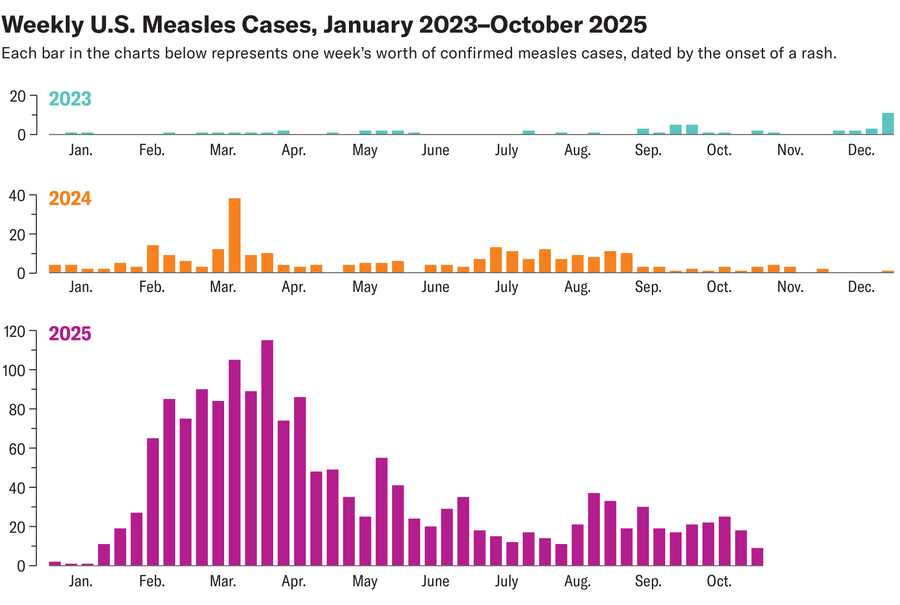

If current trends continue, North America could soon become a hotspot for permanent measles transmission. Canada could lose its measles-free designation this week, and the U.S. may not be far behind.

A key measles and rubella committee of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) will meet this week to discuss whether North American countries have lost their measles elimination status, meaning the measles virus has become endemic in those nations. A country is considered to have endemic measles if there has been uninterrupted transmission from a single outbreak of the virus that has lasted 12 months or longer.

Canada has likely already passed that milestone; the country has seen a single outbreak of more than 5,100 measles cases since October 2024, according to its health data. The U.S. is also on shaky ground. A 762-case outbreak in West Texas that started in late January 2025 was declared over on August 18. But health officials are investigating ongoing outbreaks in South Carolina and Utah. If the investigation can link those outbreaks to the original cases in Texas, and if health authorities can’t bring them under control before January 2026, the U.S. may lose its measles elimination status as well.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“I expect we will lose our elimination status,” says David Higgins, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “We are marching right toward that.”

Experts make these determinations by reviewing epidemiological data about outbreaks, as well as molecular data that can determine whether individual viruses belong to the same transmission chain, says Jon Kim Andrus, chair of PAHO’s regional verification commission. The commission also looks at a country’s vaccination coverage and its ability to detect measles cases. If there are regions where public health officials never report illnesses with rashes and fevers, for example, that’s a red flag that measles could be spreading undetected. The commission also looks at each country’s ability to strengthen its public health system and the sustainability of its programs. The process is “rigorous and detailed,” Andrus says.

Canada first eliminated measles in 1998, and the U.S. did so in 2000. In 2016 the entire region of the Americas declared the disease eliminated, but outbreaks in Venezuela in 2017 and in Brazil in 2018 reversed that declaration. Last November PAHO determined that both countries had successfully interrupted transmission, making the Americas measles-free again.

Measles can have serious long-term effects, including hearing loss, diminished immunity from previous infections with other viruses and pneumonia. One out of every 1,000 measles cases cause encephalitis, which can lead to permanent brain damage or death, says Lisa M. Lee, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Virginia Tech and a former official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The U.S. has seen more than 1,600 cases and three confirmed deaths so far this year.

“Seeing this happening right now in the U.S. is really heartbreaking,” Lee says.

Efforts to control measles are well worth the cost, says Kimberly Thompson, founder of Kid Risk, a nonprofit that focuses on pediatric risk analysis. Thompson’s work suggests that the net economic benefits of investments in measles and rubella vaccinations in the U.S. come to $310 billion and $430 billion in avoided treatment costs for measles and rubella, respectively. That doesn’t include additional gains in economic productivity gleaned from parents and kids avoiding sick days.

“It’s a huge return on investment, not just on the financial terms, but the health returns are also really substantial,” Thompson says.

The challenge is that measles is absurdly transmissible. In an unvaccinated population, each case can spawn between 12 and 18 new cases, says Amy Winter, an epidemiologist and biostatistician at the University of Georgia. Winter and her colleagues calculate that, with 84 percent vaccine coverage, each case can still cause two to three new cases—a transmissibility akin to that of seasonal influenza or the original COVID variant. That’s why 95 percent vaccination coverage is the threshold for herd immunity—the point at which there are enough people who are immune for a population to prevent ongoing disease spread.

Unvaccinated individuals are driving the U.S. outbreaks, Winter says. The solution is to increase the number of kids who are up to date on their measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) shots. To achieve that, public health authorities can expand access to vaccine clinics and ensure patients get reminders when they are due for vaccinations, says the University of Colorado’s Higgins. Pediatricians and family doctors are on the front lines of the effort, addressing parents’ vaccine hesitancy and concerns.

In the U.S., the CDC has been responsible for coordinating nationwide public health responses to measles. The Trump administration has proposed cutting the agency’s budget by $5 billion, and more than 3,000 staff have been fired or resigned since January. Most of the CDC is currently shut down, along with the rest of the federal government.

In that sense, the loss of the U.S.’s measles elimination status could be an alarm bell that the country is losing its capacity to handle public health threats.

“If you cannot stop measles transmission,” Andrus says, “how do you expect to respond to the next pandemic?”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.