Ancient Egyptian royal cemetery guards may have relied on an ear-splitting accessory to signal suspicious behavior. According to archaeologists writing in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, a 3,300-year-old cow toe bone excavated among the ruins at the city of Aketaten likely functioned as a high-pitched whistle for patrolling police. If true, the small security accessory is the first of its kind discovered in an Egyptian dynastic context, and suggests the need for further investigations into the kingdom’s other potential osseous technologies.

Located about 194 miles south of Cairo, Akhetaten was founded in 1346 BCE under the direction of Pharaoh Akhenaten. The city briefly served as the late Eighteenth Dynasty’s capital until the king’s death in 1332 BCE. Akhenaten himself is most famous for attempting to institute a proto-monotheistic religion known as Atenism. The kingdom didn’t respond favorably to a theology centered on the sun god Aten. Akhenaten earned the moniker of the “Heretic King,” and his name was stricken from historical records after his death.

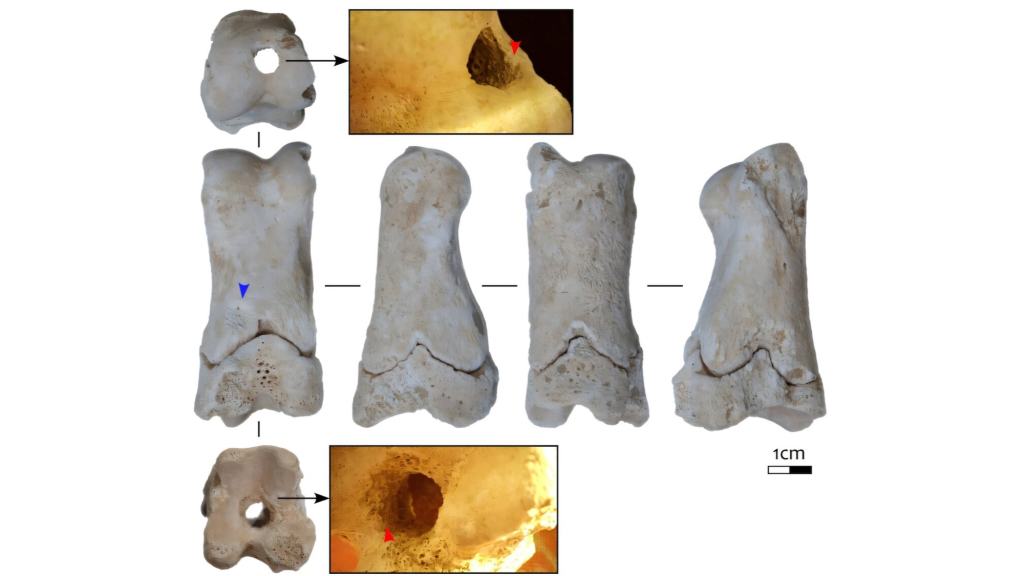

Today, Akhetaten remains an invaluable locale in the larger archaeological site of Amarna. In 2008, researchers discovered a roughly 2.75-inch-long cow toe bone inside a building located in a worker settlement known as the Stone Village. Experts identified the bone as belonging to a juvenile animal and documented a single, drilled hole bored through its length.

The relic remained in storage for years until archaeologists with the Amarna Project received the opportunity to reexamine the specimen. Using both macrophotography and microscopy, the team analyzed its overall wear and markings, then compared the object to similar examples found elsewhere around the world.

They soon had a theory about its purpose, but could only test their hypothesis by creating a replica. After acquiring a new cow bone, the researchers bored a similar hole and blew into it. The clear, loud single note that sounded from their recreation appeared to confirm their hypothesis: the artifact was likely a whistle.

The team’s argument is further supported by the site where it was originally found, as well as other contextual clues. The Stone Village was located near a royal cemetery that would have often been filled with workers. The whistle’s ability to produce a single tone rules out the possibility of being a musical instrument, while its relative lack of wear points away from its use as a game piece. The study’s authors also argue that the building in which the bone was found may also have been a guard station or sleeping quarters. Given ancient Egypt’s extensive history of tomb robbing, royal burial sites likely hosted designated security staff that oversaw workers and enforced the law.

“This small artifact, when contextualized against the archaeology and landscape of Amarna’s eastern border, is a reminder of the potential sensorial and psychological aspects of social control in an everyday setting,” the team wrote in their study.

The authors also expressed hope that their find may help spur closer looks at how ancient Egypt used bones as tools, instruments, and other implements.

“Despite over 200 years of intensive academic interest in Pharaonic Egypt, little focus has been given to understanding the production, use, and diversity of the osseous material culture created by this enigmatic culture,” they wrote.