They’re big, they appear early in the history of the universe and where they come from has long been a mystery. Ever since astronomers first detected the existence of supermassive black holes at the center of most galaxies, it has been difficult to fully explain their origin.

But a recent observation with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could help solve the riddle of how supermassive black holes grew so rapidly to become the early universe’s goliaths.

The black hole in QSO1 was first analyzed in February 2024, which revealed that the galaxy contained a black hole with a mass roughly equivalent to 50 million suns.

A recent follow-up study led by Ignas Juodžbalis from the University of Cambridge confirmed the original mass estimate and also showed unequivocally that QSO1 lacks a significant component of gas and stars. Instead of being a black hole that sits at the center of a galaxy, it’s as if the black hole itself is dominating the system and the wider galaxy is missing.

“It’s a very odd system,” Marta Volonteri, a professor at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, said in an interview with LiveScience. “If there are more like that, it becomes really bizarre.”

Volonteri is a world-leading expert on the formation of supermassive black holes and contributed to the analysis of the black hole’s mass. “I double checked the results with my own code. There is very little room for any substantial mass in the system besides that of the black hole,” she said.

In QSO1, the black hole’s mass is about twice that of the surrounding gas and stars. In contrast, the black hole Sagittarius A*, which sits at the center of the Milky Way, has a mass that is only a tiny fraction of the total mass of the galaxy.

Mysterious little red dots

As JWST began gathering data in 2022, it revealed a surprising discovery: numerous compact, red-hued galaxies dubbed “little red dots” observed at epochs corresponding to roughly 500 million to 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

Their exact nature is still a mystery, but these ancient systems seem to indicate that galaxies, black holes or both evolved earlier, and with greater masses or densities, than astronomers had previously believed.

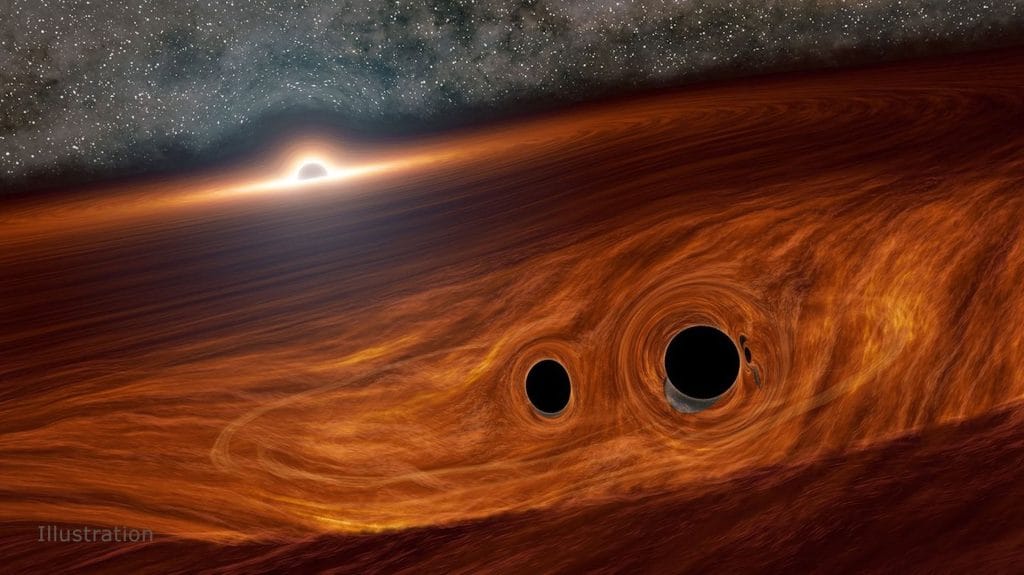

Black holes can form when massive stars exhaust their nuclear fuel and collapse under their own gravity. At the dawn of the universe, these early black holes would have grown by feeding on a buffet of stars, gas clouds and other black holes. Yet when astronomers calculate how quickly such stellar-mass black holes could accrete matter, they find it difficult to explain how they could have grown into the cosmic behemoths observed by JWST.

One alternative scenario is that instead of being created from stars, some early-universe black holes could have been formed from the direct collapse of huge gas clouds with much larger masses. Such a scenario was supported by the discovery of UHZ-1, a black hole that displays the telltale signs of direct collapse according to a study led by Priyamvada Natarajan from Yale University.

But the system QSO1, one of the several hundred little red dots that astronomers have analyzed, seems to have formed in a different way.

“My co-authors suggested that its origin could be a primordial black hole, or it may be dark matter that has collapsed because of how it interacts with itself,” Volonteri said. “In any case, the black hole came well before the ordinary matter, such as the gas and the stars.”

Primordial black holes

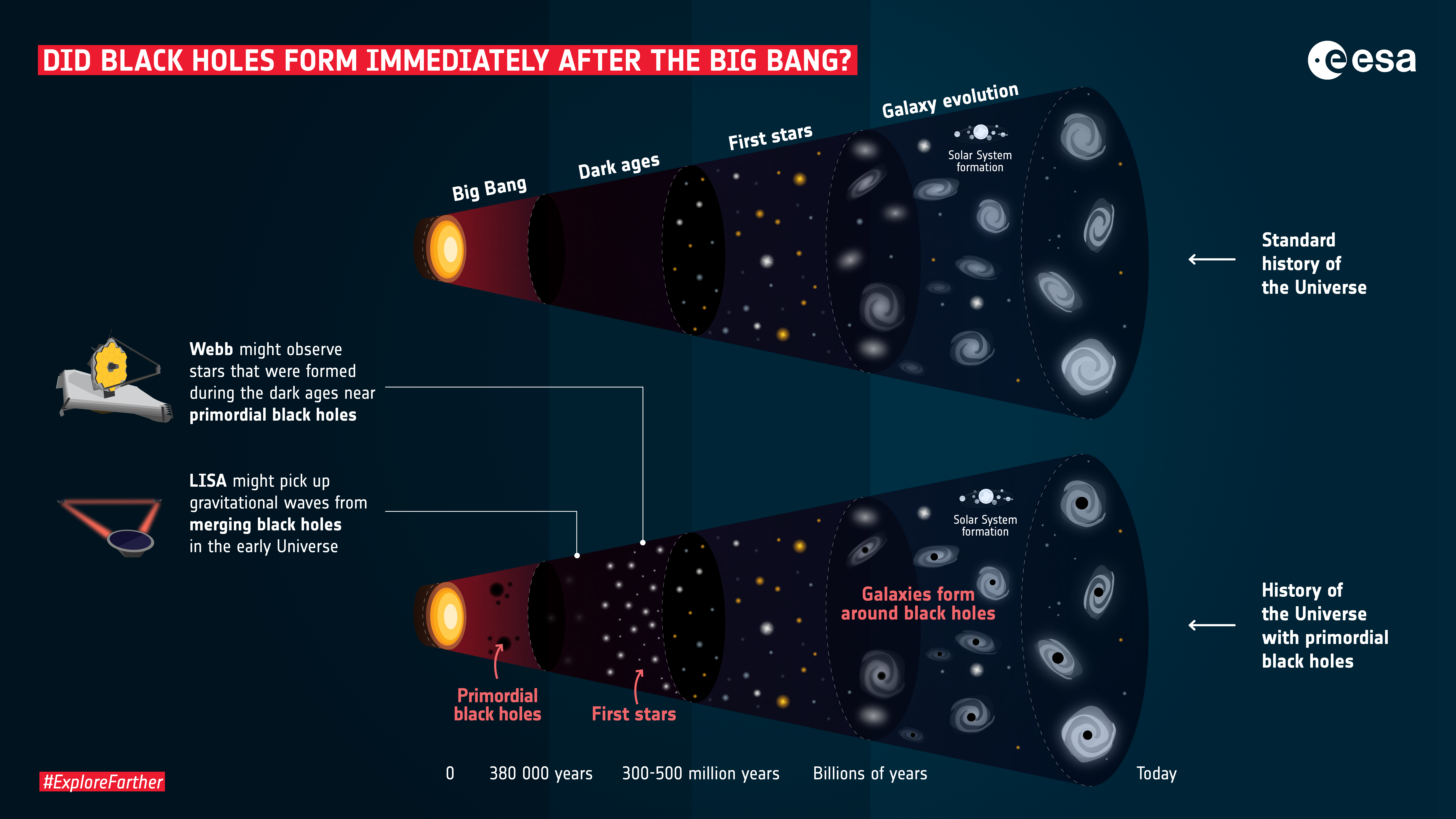

In 1967, the Soviet physicists Yakov B. Zeldovich and Igor D. Novikov proposed that, for a brief moment after the Big Bang, some regions of the universe contained so much mass that they imploded into black holes. The idea was further developed by Stephen Hawking in 1971, and has since been investigated both theoretically and observationally by several astrophysicists.

These primordial black holes would not only get a head start in terms of their growth and size, but also sit dead center in the galaxies that form around them. “That the black hole in QSO1 grew so much without any star formation taking place points to a case in which it developed significantly faster than the galaxy,” Volonteri said.

The question, then, is if the discovery of QSO1 solves the chicken-or-egg problem of which came into being first: the galaxy, or the black hole at its center?

“This is one object that is still being reviewed. I hope that all this analysis is correct, but it’s very complex. But what we used to call exotic models are perhaps not so exotic anymore,” Volonteri concluded.

Marta Volonteri was previously interviewed by the author for the book Facing Infinity: Black holes and our place on Earth, which contains more information about her work and the origin of supermassive black holes. Read an exclusive excerpt here.