Despite the Trump administration’s insistence that the U.S. must win a race back to the moon with China, NASA looks increasingly unlikely to succeed, experts say. Meanwhile China insists it isn’t in a race at all yet looks poised to win the 21st century’s lunar scramble.

The first Trump administration unveiled its Artemis lunar landing program in 2017, aiming for astronaut boots on the moon in 2024 and an eventual “Artemis Base Camp” a decade later. These would not be Apollo-style flags-and-footprints sorties but rather longer-duration missions meant to support the construction of an eventual Artemis Base Camp lunar outpost; as such, they require bigger rockets and spacecraft—and more complex hardware for surface operations. After a long delay, the program’s first crewed lunar flight, Artemis II, is scheduled for next year sometime between February and April. Launched by the space agency’s costly Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, the mission will fling four astronauts around the lunar orb and back to Earth. It will be the first human mission to—albeit not on—the moon since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Actually landing U.S. astronauts on the moon is officially slotted for 2027, on NASA’s Artemis III launch. The only problem is that former and retired space agency officials are now publicly calling that timing unlikely. The effort comes as China makes steady progress on its own lunar program. In August the China National Space Administration test-fired the first stage of its own lunar rocket, aiming to place people on the moon by 2030. And that nation’s timeline is looking a lot more realistic than ours, space experts say. At stake are not only bragging rights, some fear, but also the ability to set the rules of the road for the future on the moon, on Mars and in the rest of the solar system.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

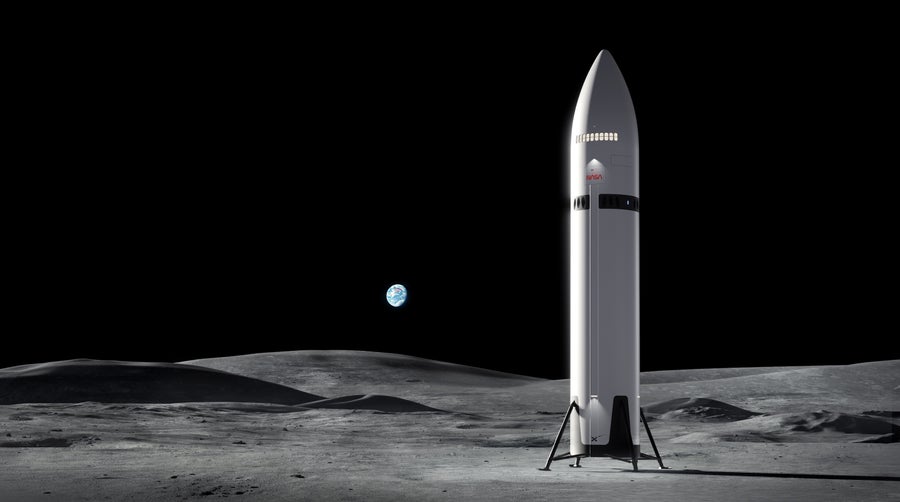

Artist’s concept showing SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System (HLS) docking directly to an Orion spacecraft.

Starship Problems

For the U.S., after years of delays on NASA’s SLS rocket and Orion capsule, the sticking point is now SpaceX’s Starship rocket, selected as the U.S. lunar lander four years ago. To send astronauts to and from the moon, Starship will have to refuel in Earth orbit and land upright on the lunar surface—capabilities that are new and untested. And it must do all that by 2027, to hit NASA’s schedule—or 2030, to match China.

Yet Starship has suffered a string of testing mishaps this year that have put it well behind schedule. It hasn’t even orbited Earth yet, let alone the moon. Skepticism for NASA’s planned timeline abounds. “Unless something changes, it is highly unlikely the United States will beat China’s projected timeline to the moon’s surface,” former Trump administration NASA chief Jim Bridenstine testified before the U.S. Senate in September. At the hearing (entitled “There’s a Bad Moon on the Rise: Why Congress and NASA Must Thwart China in the Space Race”), he summed up many experts’ frustration with the plan: “the complexity of the architecture precludes alacrity.”

His views echoed those of three former NASA officials—Douglas Loverro, Doug Cooke and Dan Dumbacher—who wrote, “it is indisputably clear that the plan for Artemis will not get the United States back to the moon before China,” in a September SpaceNews editorial. They called for a “Plan B” for beating China to the moon.

NASA’s acting chief, Sean Duffy, the current secretary of transportation, reacted with anger to the criticism. “I’ll be damned if that is the story that we write,” Duffy said at an agency town hall meeting. “We are going to beat the Chinese to the moon. We are going to do it safely. We’re going to do it fast. We’re going to do it right.”

His response anticipated a Senate committee report’s warning that the Trump administration’s plans for NASA, large cuts to science and single-minded turn to landing astronauts on the moon and Mars puts astronaut’s lives at risk. Fears of firings have hurt the agency’s safety culture alongside “muzzling” of NASA’s ombudsman program, according to the report, echoing a point also made in the “Voyager Declaration,” a July letter to Duffy from agency employees, many anonymous for fear of retaliation. They decried prioritizing “political momentum over human safety.”

Later in October, Duffy conceded Starship was falling behind schedule, and said that NASA wanted to get “back to the moon in 2028,” pushing the schedule backwards while looking for alternative rockets. “The president and I want to get to the moon in this president’s term, so I’m going to open up the contracts,” he told CNBC.

Artist concept of SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System (HLS) on the Moon.

One-Sided Moon Race

Yet despite U.S. angst over the “race,” China shows few outward signs of viewing space exploration as a contest.

China doesn’t even see itself as in a race to the moon, says planetary scientist Yangting Lin of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “I believe that promoting the ‘China threat’ theory and the idea of a space race is, in part, intended to secure funding from Congress.”

“I think we need to grapple with whether we care about China and the moon,” says former NASA associate administrator for science Thomas Zurbuchen (who is on the science advisory board of SpaceX competitor Blue Origin). “We won that race. Why declare a second one?”

Some of NASA’s current problems can be blamed on changing administrations and changing yearly appropriations from Congress, “rather than any one decision or one person,” says Planetary Society co-founder Louis Friedman.

In 2010 the Obama administration killed the George W. Bush–era Constellation plan for NASA to return astronauts to the moon, proposing instead to send crews to an asteroid as a pathway to eventually reaching Mars. Despite changing destinations, however, politics ensured that Constellation’s most costly and problematic components endured—namely, its crewed Orion capsule and a heavy-lift rocket based on vintage space-shuttle tech. Rebranded as the Space Launch System, that much-derided rocket and the Orion capsule were forced on successive administrations by space-state lawmakers in the U.S. Senate. SLS is now years behind schedule and carries single-launch costs of around $4 billion.

Enter the first Trump administration in 2017. Bridenstine subsequently pushed the Artemis program to get astronauts back on the moon using SLS rockets and the Orion capsule. Next came the Biden administration, which maintained support for Artemis but in 2021 decided that SpaceX’s still-developing Starship would be its first moon landing vehicle, citing cost savings over developing its own NASA lander.

Finally, the second Trump administration first sought to kill off SLS but now appears poised to compromise with Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, who is intent on keeping the jobs-delivering-program alive, at least through an Artemis V launch.

“A Very Complicated System”

Inside NASA, senior leadership has long understood the agency stood slim odds of beating China’s target date for a moon landing, says former agency chief scientist James Green. “It was obvious to us more than a year ago that we’re not going to make 2030. Now why is that? Because we’ve got a very complicated system.”

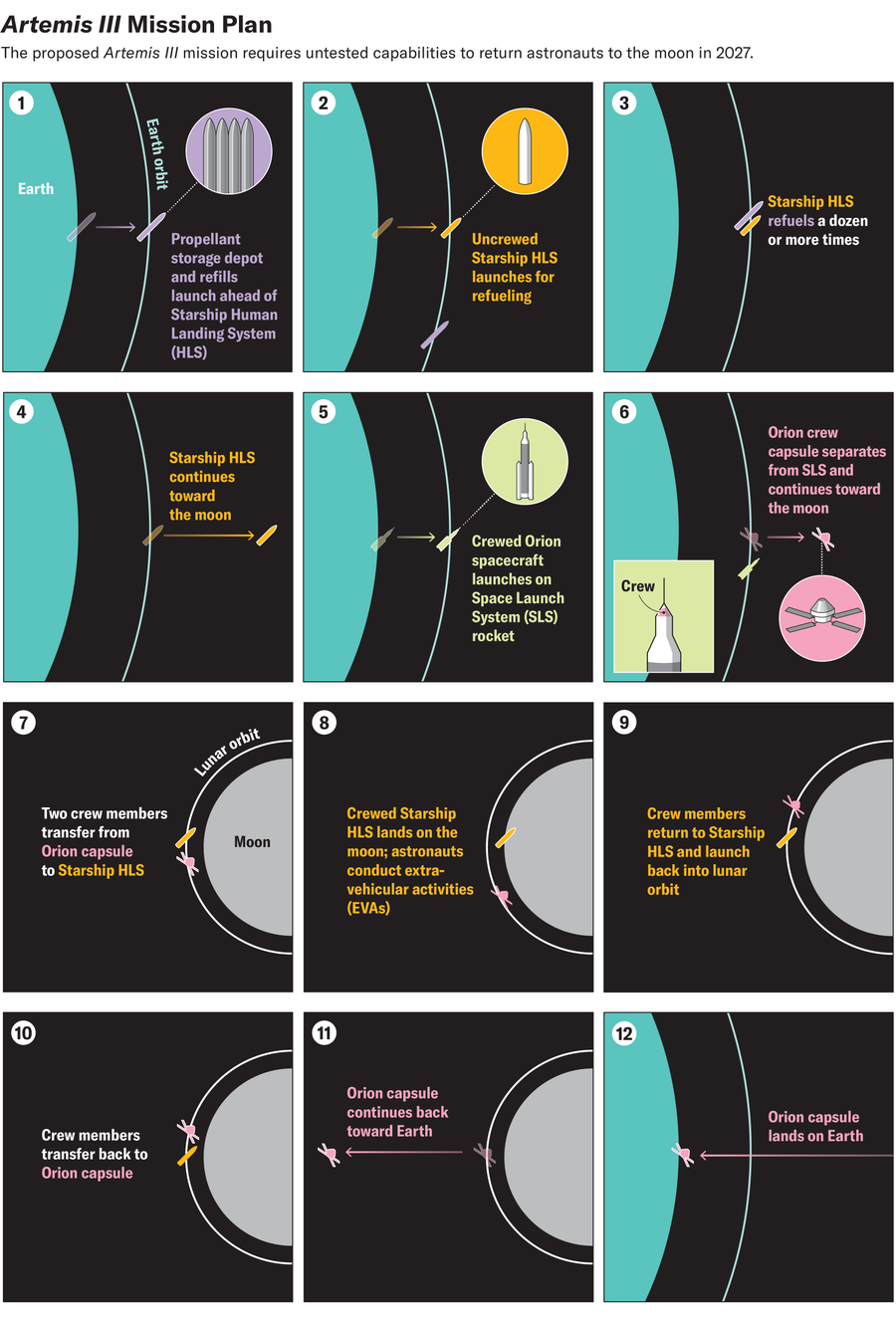

NASA seems to be following a Rube Goldberg–themed template for its moon missions: An empty SpaceX Starship lander, built under a $2.89 billion contract, would first launch into orbit around Earth and then refuel a dozen or more times in space—a completely untested feat—before heading to the moon. A NASA SLS rocket would next launch a Lockheed Martin and European Space Agency–built Orion capsule carrying astronauts to the moon. The Orion capsule would rendezvous with the Starship in orbit around the moon and transfer two astronauts. Starship would then land upright on the cratered lunar surface—another untested feat—disgorge and collect the astronauts (via a 15-story elevator) and then blast off to reunite them with their orbiting capsule for a trip home.

The space firm hopes to launch an upgraded Version 3 Starship into orbit next year to test the basis for its moon lander. It will also need to show Starship’s upper stage is safe for human flight, pioneer refueling it in space and demonstrate that one engineered as a lunar lander can safely touch down (upright, as in a 1950s science-fiction movie) on the moon and take off.

That last hurdle, safely landing a SpaceX Starship HLS (Human Landing System) spacecraft, carrying two astronauts, upright on the moon, particularly troubles Green. “We have not done the analysis, in my opinion, to determine if you could actually land a massive Starship on the moon,” he says.

Landing anything on the moon isn’t easy, as demonstrated by Apollo 11’s nail-biting touchdown, in which the Lunar Module Eagle overshot the landing site leaving only minutes of fuel to find a safe landing spot, as well as by recent Athena mission overturned landings. The moon is covered with about 10 meters of regolith, a mix of dust, ash and rocks punctured by craters and boulders—not pristine landing pads. Landing a Starship, 15 stories tall, upright on the moon’s rugged south pole will require firing rockets into that regolith, creating a small crater at the landing site. Too much landing thrust could burn into the regolith, punching a destabilizing hole in its loose surface. NASA only started testing simulated Starship landings on artificial regolith on Earth in April.

NASA’s safety advisory panel, meanwhile, thinks the time needed to demonstrate successful on-orbit refueling of a Starship HLS will means it will be “years late” to carry anyone to the moon.

Illustration of propellant loading operations in Earth orbit of a Starship HLS.

Plan B

Many are hoping for a “Plan B” alternative to the current Artemis moon landing architecture. Whatever form that plan takes, it will have to start with the SLS rocket, Green says. Whatever its faults, that vehicle has at least demonstrated it can carry a space capsule to the moon.

To save money and time, Ars Technica’s Eric Berger has suggested the space agency kill a costly add-on to SLS, the still-under-development Exploration Upper Stage rocket intended for Artemis lunar missions, and replace it with something cheaper, such as the Centaur V used since 2014 to boost massive spy satellites into high orbit.

And NASA could build a simpler, modern-day, Apollo-style lunar module landing craft, Green suggests, as an alternative to waiting for a Starship HLS. That might provide work at NASA centers such as Alabama’s Marshall Space Flight Center, which would suffer job losses as future SLS missions are turned off.

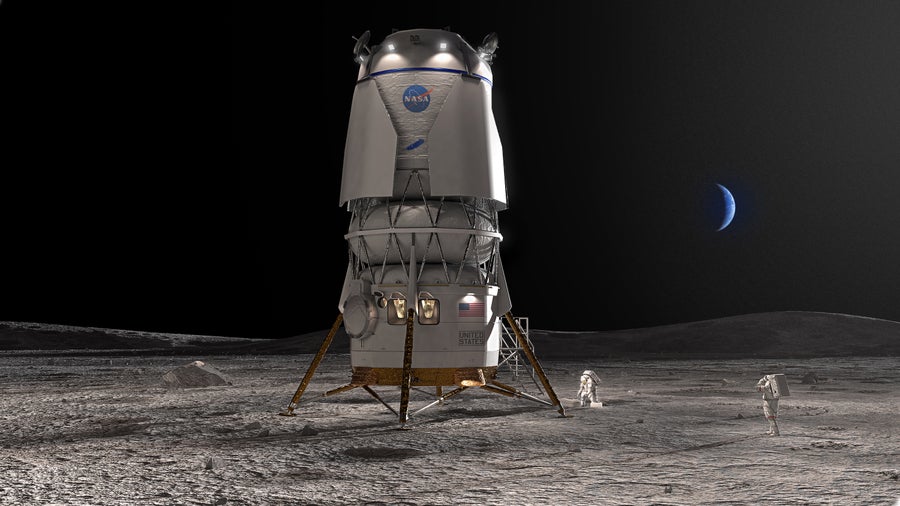

Artist’s depiction of a Blue Origin lunar lander on the moon.

NASA’s September revival of the VIPER science rover intended to explore the lunar south pole also suggests another alternative lander for moon missions, one built by Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin rocket company. Blue Origin’s Blue Moon Mark 1 lander, now in production, is due to deposit the rover to the lunar south pole in late 2027. NASA has already selected a Blue Origin lander for the Artemis V mission in 2030, though that plan still hangs in the balance of the budget face-off between the Trump administration and Senator Cruz. The design of the Blue Origin lander is a lot more “traditional,” Zurbuchen says, resembling a larger Apollo lunar module.

Blue Origin’s Mark 2 is set for an uncrewed test landing on the moon in 2027 as a test run for Artemis V. Plan B might see Artemis III swapped with a reduced Artemis V mission to win the self-declared moon race while waiting for Starship to prove out for bigger, heavier missions. In his recent call for a 2028 landing, Duffy specifically mentioned Blue Origin as an alternative to SpaceX for moon landings.

NASA’s entire moon plan is just way too complicated, Friedman says. “The basic question is, why are we rerunning a race to the moon to lose it?”