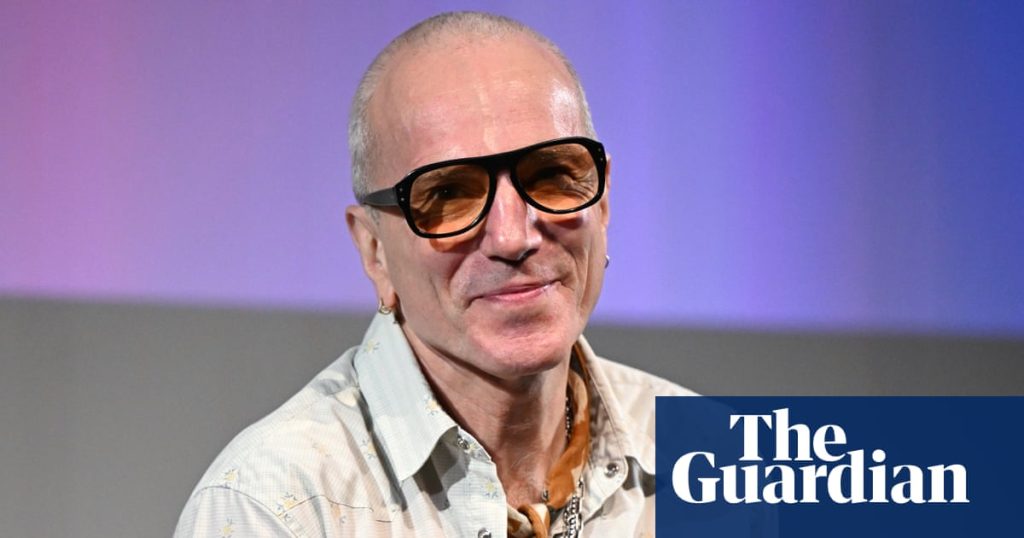

The actor Daniel Day-Lewis railed against audiences being priced out of theatres, and what he perceived as a continued snobbery concerning cinema in the UK at an event at the London film festival.

Speaking to the critic Mark Kermode for a lengthy conversation in front of an audience at the BFI Southbank, Day-Lewis said he felt “there’s still an elitism in this country that theatre is the superior form”. His drama training at the Bristol Old Vic school had encouraged in him the sense that theatre work was the goal. “Then there’s films: bit dodgy. Television: like, really? OK, you gotta pay the gas bill. That was the thinking.

“There was no concession [in the training] to movies at all. But secretly, most of us [students] longed to make movies, because we’d been raised on movies, and movies seemed just so wonderful to us and magical.

“Not that the theatre isn’t too, but the theatre in itself is an elite cultural form. There are of course exceptions, many wonderful theatre companies that manage to put on affordable performances for everybody. But the great thing about the cinema is that everyone could – maybe not so much these days – but everyone could buy a ticket.

“Theatre essentially relies on people having had the privilege of an education that allows them to believe that they’re entitled to go to the theatre. And that education has enabled them to understand perhaps the classics in a way that they make sense to them. It’s a relatively small group of people that is available to, and that is just quite wrong. It always bugged the hell out of me, much as I loved my time in the theatre, that we were essentially performing to a group of more or less privileged people.”

On Tuesday night, Day-Lewis attended the UK premiere of his new film, Anemone, which as well as starring in, he has co-written with his son, Ronan Day-Lewis – who directs. The film is the three-time Oscar winner’s first movie in seven years, after his withdrawal from the profession in 2017.

Following the release of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, representatives for Day-Lewis released a statement saying he “will no longer be working as an actor … This is a private decision and neither he nor his representatives will make any further comment on this subject.”

Speaking to Rolling Stone last month, however, Day-Lewis declared that he “never intended to retire” and “would have done well to just keep [his] mouth shut”.

During the conversation, the actor again rejected what he perceived as misconceptions about method acting, saying that “recent commentary” about the technique for which he is famed “is invariably from people who have little or no understanding of what it actually involves. It’s almost as if it’s some specious science that we’re involved in or a cult.”

“It is very easy to describe what I do as if I’m out of my mind and plenty of people have been happy to do that,” he said, adding that people often believed he was “mad as a March hare.”

Rather, he said, method acting is “just a way of freeing yourself” in order to be spontaneous and “able to accept whatever passes through you” as another person. As an example, he cited one of Anemone’s key monologues, in which recounts to his brother (played by Sean Bean) how he exacted revenge on a clergyman who had abused him as a boy, with the help of Guinness, curry and a box of laxatives.

“I don’t know why I found it so funny,” he said. “The idea of shitting on a priest. It’s not normal. But I just thought it was it hilarious and couldn’t stop laughing.”

He also discussed the role for which he won his first Oscar: the artist Christy Brown, who had cerebral palsy, in Jim Sheridan’s My Left Foot. The sea-change in attitudes toward the portrayal of people with disabilities in the 36 years since that film was shot meant he would no longer be cast in the role, said Day-Lewis.

“Quite obviously, I would not be able to make that now, and for good reason – at the time it was already questionable,” he said, adding that “a couple of the kids that helped me so much at the Sandymount Clinic [for people with cerebral palsy] made it clear to me that they didn’t think I should be doing it.”

The actor prepared by spending two months in a house with a wheelchair and a set of paints. “If you’ve got the responsibility of portraying a life like Christy Brown – a huge and noble figure in Irish society – then you should to try to understand as far as you are humanly able what it feels like to be inside of that experience. And I thought: ‘I’m never not gonna work like this again.’”

Day-Lewis reflected that before making My Left Foot he had been “clueless” about moviemaking. “I didn’t have a fucking clue what I was doing,” he said, recalling the exasperation of director Stephen Frears on the set of My Beautiful Laundrette when shooting a scene in which his character is cleaning the shop.

“There’s something like a compulsive need to find something that feels real to me,” he said. “So I’m mopping the floor and he says: ‘Just keep doing that.’ I said: ‘That bit’s clean.’ Stephen is a very clever man but he has very low tolerance. So he sent me to the cutting room with the editor and I’m looking at [the footage] and I go: ‘Oh, I see. Right. Because you need to be in the frame … ’ I was that stupid.”

Day-Lewis, who also won best actor Oscars for There Will Be Blood in 2007 and Lincoln in 2012, also discussed working with his wife, the writer-director Rebecca Miller, on 2005’s The Ballad of Jack and Rose. She had sent him the script 15 years earlier, he said, before they had met.

“I was very fond of her mum [photographer Inge Morath] and dad [the playwright Arthur Miller] and I got to know them and would go and stay with them in the house that Rebecca grew up in. So I heard a lot about her. And she sounded all right.”

Working with their son, Ronan, 27, on Anemone was a similarly happy experience, he said, propped up by a generous director with time for everyone. “You can’t guarantee you’re gonna get a great film out of it, but what you will get is an experience that people will always remember happily. That was true of Jack and Rose, and it was true of Anemone.”

The film, set in the late 1980s, is about two brothers, Ray (Day-Lewis) and Jem (Bean), who both served as British paramilitaries in Northern Ireland years before. Day-Lewis said that while some of his previous films, including In the Name of the Father and The Boxer, had looked at the debate from the perspective of West Belfast Catholics, there was a sense in which it was “not really cool to show the British military experience because they were the bad guys when in that situation.

“But that’s not how it was. It was like anywhere in any conflict. There were young working-class people pitched against each other usually for no good reason. It was a dirty, dirty conflict. And I’d only really examined it from one point of view.”

Anemone has met with mixed notices, with critics praising Day-Lewis’s performance and the film’s stylistic ambition, but less certain on whether it adds up to a coherent piece of cinema.

The film’s reception did bother him, said Day-Lewis. “You sort of try and wear a cap of defiance but it doesn’t fit that well. ‘We made this film we were happy making, it is what it is, we did what we could, we did our best etc.’ And of course it matters hugely to us.

“The critics to some extent do have the power to either encourage people to see it or discourage them from seeing it. They’re the middlemen and women between us and the public. But what of course we yearn for is that when our job is done, that it will be meaningful to people. And if it proves not to be, it’s a very, very bad feeling. It’ll bring you right down.”

But both he and his son cautioned against attempting to cater to public taste. “If you are trying to second-guess what people will think and how they’ll react,” said Day-Lewis, shaking his head. “There’s an epidemic proportion disease in cinema of that: trying to figure out how to get the audience to laugh, get them to cry, get them to whoop and cheer.”

Day-Lewis also recalled interactions with his own heroes of acting, including Marlon Brando, who once proposed working together, and Alec Guinness, who wrote to him with praise after the release of My Beautiful Laundrette. “That just meant the world to me.”

He added that the most powerful screen performance he had ever seen was that of the first-time child actor David Bradley in Ken Loach’s Kes, saying “I didn’t know it was possible to do something like that. A young boy who’d never acted before. And it is true and a little bit demoralising that some of the great performances over the years are from people who have never trained.”

Day-Lewis reminisced about his years spent attending Saturday morning picture club screenings in south London: “You’d see cartoons and then the Lone Ranger and then something in a spaceship and they’d give you a badge and it was just fantastic.”

He also named Mary Poppins as one of the greatest films ever made, singling out its star for particular praise, saying: “What a doll. I had a crush on Julie Andrews.”

Reflecting on his career, Day-Lewis said that while “proud of a few things, a lot of things I’d start from scratch”. But in retrospect he was relieved, he concluded, that he’d possessed the “certain steadiness” which enabled him to turn down many more projects than he took on.

“I’ve done very little over the years, but I knew from an early age that I wouldn’t try to dance to somebody else’s beat.”